Markup Pricing

MARK-UP PRICING:

A DISTORTER OF TRUE COSTS;

AN OBSTACLE TO PROGRESS;

AND AN EXPORTER OF AMERICAN JOBS

by

Argus C. Zall

INTRODUCTION

The practice of allocating costs to products traversing the distribution chain from factory to retail customer by “marking up” by a fixed percentage the price at entry at each stage to obtain the price at exit is extremely common throughout American business. It is the simplest way to allocate the costs of each stage, which although known in total for the entire assemblage, are presumed not to be known individually. It made a great deal of sense in the 1800’s, when the markups were only a few percent, and the only computing instrument was green eyeshade and a lead pencil.

It makes no sense today. The costs to be allocated amount to some eighty percent of the retail price to be paid. The typical “total direct cost” of manufacture (material plus direct labor plus direct labor overhead) of a mass-produced and distributed product is often as little as 10% of the “manufacturer’s suggested retail price” (“MSRP”). To the total direct cost are added numerous other costs; factory period costs, shipping and warehousing costs, wholesaler’s break-bulk costs, distributor’s costs, retail stocking costs, display costs, advertising costs, transaction costs, etc. etc., etc. All of these costs are allocated, typically by markup pricing. The appropriate markup ratio is the total added cost to be allocated, divided by the total product entering value, typically expressed as a percentage. Markups of 40% and more are common.

Taking total direct cost of 10% and allowing for a profit of 10% means that 80% of the MSRP represents allocated costs. The assumption of mark-up pricing is that each of these costs at every stage is proportional to the total value of the product entering that stage. As I will show in more detail presently, this assumption is usually false. Once the goods leave the factory floor, true costs usually bear no relationship to product price.

Since the pioneering time and motion studies of Frank Galbraith around the turn of the last century, and the development of the profession of Industrial Engineering, it has been possible to determine quite accurately the cost of materials and direct labor to manufacture a single product on the factory floor. This is the first, last, and only place in the entire distribution chain where American business has the slightest idea of the true cost of doing any one thing. Starting with direct labor overhead, every other cost down the chain to the customer is a cost allocated by markup. As I will show below, in a distribution chain that involves many products having different values, this leads to grave distortions in allocations. Furthermore, it attaches enormous importance to the total direct cost; since each cost is a markup from all the other costs that preceded it, the total direct cost ultimately determines the MSRP, even though it amounts to only 10% thereof.

EXAMPLE OF MISALLOCATION

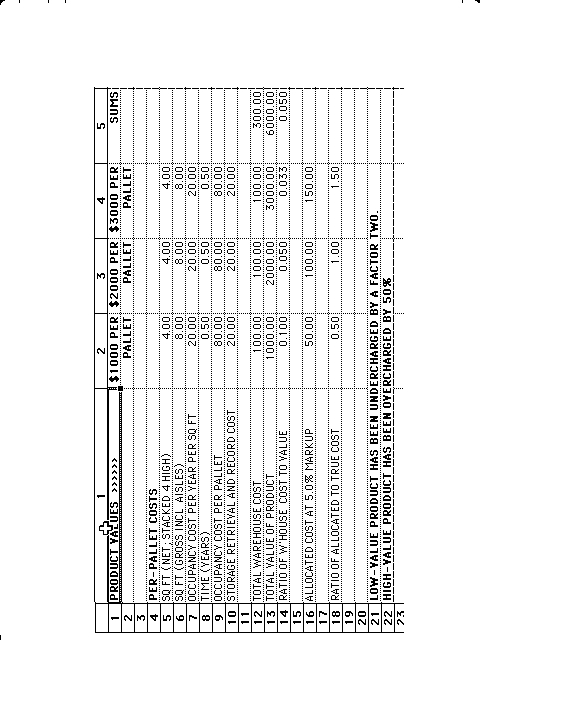

As an example of the misallocations that occur, consider the warehousing of a family of products A, B and C. A is the least expensive, with a pallet load (4’ x 4’ x 4’, 64 cubic feet) accommodating only $1000 worth of goods at entry to the warehouse.. B is more valuable at $2000 per pallet load, and C is the most expensive at $3000 per pallet load. Assume equal numbers of pallets of the three products pass through the warehouse. Under markup pricing, product C will be charged one half the total warehouse costs. This is a particularly egregious case, because the true costs are simple to calculate.

As shown in Table I, the cost of warehousing is the cost of occupancy per square foot per year, times the square footage occupied, times the fraction of the year it is occupied, plus the cost of storage, retrieval and record-keeping. The basic unit being a pallet, and a pallet being a pallet being a pallet, these costs are the same for each pallet, whether of product A, B or C. In the examples shown, this is $1001 . The total cost being $300, and the total value being $6000, the markup pricing allocation is 5%. On this basis, product A is allocated $50 per pallet warehouse cost, product B is allocated $100, and product C is allocated $150. Product A has been undercharged by a factor two, while product C has been overcharged by 50%.

TABLE 1

Although this may seem like a picayune splitting of hairs, similar things happen all the way down the distribution chain when costs that bear no relationship to product value are allocated as if they were proportional to it. The net result is that under markup pricing the most expensive products in a mixed chain bear the lion’s share of the costs, and the least expensive products are subsidized. Since the allocated costs amount to 80% of the MSRP, this allocation error grossly distorts the ultimate MSRP and the retail price actually paid by the customer.

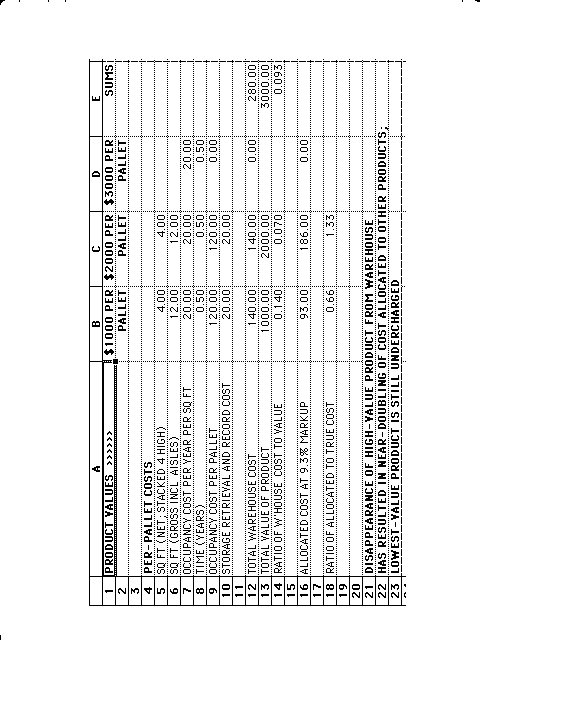

Consider, in Table II what happens to this picture when, because of misallocation of costs, the selling price of product C becomes so high that it is priced out of its market and is no longer able to compete with lower cost alternate products. Product C disappears from the market and no longer traverses the distribution chain. In Table II, note that the gross square footage formerly occupied by product C must now be charged to products A and B, since the warehouse is not expandable/collapsible to accommodate space needs; the occupancy cost formerly borne by product C must be covered by the other two. I have assumed, however, that the labor costs associated with storage, retrieval and record-keeping of product C can be eliminated by layoffs. Thus, the total warehouse cost to be allocated is $280 while the product value has dropped to $3000. The markup must now be 9.3%, so the costs allocated to both remaining products nearly double. However, product A is still charged less than the true cost of its warehousing, while product B is overcharged by 33%. If both of them had been charged real costs in the first place, their costs would have only gone up 40% upon the loss of product C.

TABLE 2

Lest it may be thought that these are exaggerated examples, I hasten to assure you that I have seen it happen in my industrial experience. The loss of an expensive product when it became priced out of business caused the allocation of costs in a multiproduct warehouse to double for the remaining products. The product managers for the less-expensive lines were completely flabbergasted by this surge. They had no idea that the expensive product was subsidizing their warehouse costs until the subsidy was cut off. The sad part about it is that if the expensive product family had not been unfairly saddled with misallocated costs throughout the product chain, its selling price could have been low enough that it might have been able to withstand competition from the alternative products.

AN OBSTACLE TO PROGRESS

Consider a product family with a total direct cost per unit of $0.10, and a retail selling price of $1.00, holding its own in a competitive marketplace. The engineers engaged in RD&E discover a product improvement that would increase total direct cost by one cent ($0.01). No other real cost down the distribution chain would be changed. Therefore the retail price should increase by one cent to $1.01. Because of the improved performance, the product is still competitive even at the higher price, and even increases market share. Right? WRONG!!! Because all costs in the distribution chain are allocated by markup pricing, the increase in retail price is TEN CENTS, and the new retail price is $1.10. At this point, even with improved performance, the product is no longer competitive in price and would lose market share. Therefore, hard-boiled business men in management squelch the improvement and send the engineers back to the labs with their tails between their legs. The increase in allocated costs of $0.09 is entirely in error, because none of those costs were actually changed by the product improvement. Faulty “facts” (no matter how many digits after the decimal point they carry) lead to faulty decisions.

Changes in product and process are made in manufacture to reduce costs, although skilled engineers can slip in product improvements at the same time. If there is not a simultaneous reduction of cost, product improvements have a difficult time getting into production.

EXPORTER OF AMERICAN JOBS

The most pernicious aspect of markup pricing is the exaggerated importance it gives to the total direct cost of manufacture in determining selling price of an item, and the effect this has on decisions to outsource production. Let me give an example.

Some years ago, when my son got a promotion, I gave him a fine leather briefcase. I studied products available in the store, eventually settling upon a choice between two identical cases: one manufactured in the US, selling for $200, and one imported selling for $100. Since the cases were nearly clones, I bought the cheaper one.

However, later I reflected on the fact that of the $200 for the US-made case, only $20 was the actual direct cost of manufacture; adding factory period costs would take the ready-to-ship cost to $40. Allowing that cheap foreign labor would permit a total direct cost for the imported case to be $10, after shipping to the US and entering the distribution chain it would be valued at $20. From that point on, all real costs for both domestic and imported products are the same!!! Shipping in the US, warehousing, distribution, display, transactions, etc., etc., all occur entirely within the US for both products; the imported product derives no benefit of low labor costs. If those costs amounted to $160 for the US product, they should amount to $160 for the imported one as well.

However, because all those costs were allocated by markup pricing, the import article was only allocated $80, giving a selling price of $100 instead of the true cost value of $180. If I had had a choice between identical US and imported products at $200 vs. $180, I would have bought the US product.

Consequently, the markup pricing system subsidizes the traverse of foreign goods through our distribution system because of their low manufacturing cost, charging them much less than the real costs of distribution and retailing. Is it any wonder that you can hardly find an article of clothing that isn’t made in China anymore? An American icon, the red Radio Flyer wagon, will now be made in China, even though the real savings is only a nickel on the dollar of selling price. The accounting fiction of markup pricing allows Wal-Mart to pretend that its cost of warehousing, distributing, and selling them is somehow magically reduced by fifty cents on the dollar thereby. Seventy-five American jobs are outsourced because of this mistake.

SHAME ON YOU, COST ACCOUNTANTS!!!

As an engineer, if I were to design a bridge the way you allocate costs, I would first ask what load of vehicles the bridge was expected to carry. I would multiply that value by my traditional (and secret) markup to determine the total weight of the bridge. Then I would decide how many struts the bridge was to be made of. Dividing one by the other gives the load each strut has to bear; engineering handbooks would tell me the size they would have to be to bear that load. And presto!, my bridge is designed. Because bridges designed using this approach would have collapsed in the past, my markup would have been made robust, and my bridge would not collapse. However, every strut in it but one would be “overdesigned”.

And I would be laughed out of the profession.

You should be too. You are using a method of allocating costs appropriate to the horse- and-buggy age, when the availability of computers and spreadsheets now makes it possible to do a much more realistic job with little or no effort.

I challenge you to do it.

February 4th, 2015 at 6:54 pm

Pregúntale: “¿cuántos triángulos rojos hay?” “¿cuántos perros grandes de color cobrizo ves?”, de manera que compare más de un atributo

de los objetos.

October 19th, 2017 at 1:13 am

watch one missed call japanese online free

Ideas from Argus C. Zall